The Cup of Water — Dachau Death March, 1945

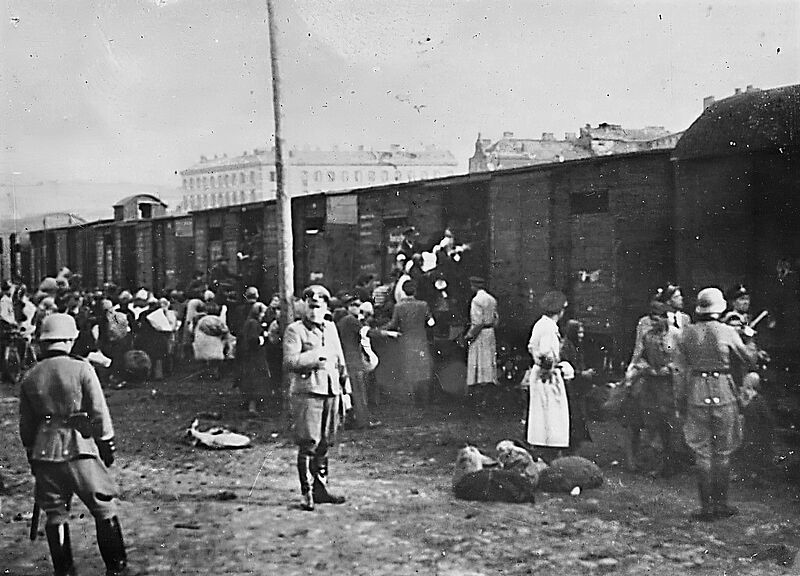

The road stretched endlessly before them, a ribbon of mud and ice winding through a landscape stripped bare by winter. The men walked in silence, their striped uniforms hanging loose on bodies wasted by hunger, their skin pale with sickness and cold. This was the Dachau Death March of 1945, when thousands of prisoners were driven from the infamous concentration camp as the Nazi regime collapsed in its final days. To many, it was not a march but a slow procession into death itself. Yet within this darkness, a single cup of water became a beacon of humanity, a fragile act of kindness that defied the cruelty surrounding them.

The prisoners trudged forward with mechanical steps, their feet blistered and swollen, their lungs burning with every ragged breath. Guards shouted orders from behind, rifles ready, their boots echoing like the drumbeat of despair. Snow mixed with mud clung to their ankles, dragging them down. Hunger gnawed at their insides, thirst seared their throats, and exhaustion turned the world into a blur of gray.

For many, hope had long since died inside the barbed wires of Dachau. The Holocaust had stripped them of families, homes, and even their names, reducing them to numbers sewn crudely onto their uniforms. And now, as they staggered across the frozen countryside, they carried nothing but the fragile thread of survival.

It was along one such stretch of road, flanked by bare trees and silent farms, that the extraordinary happened. A child, no more than ten years old, stood at the edge of the road. He was not supposed to be there—villagers kept their distance from the prisoners, fearful of punishment. But children, with their instinct for compassion unclouded by politics or fear, often see what adults choose to ignore.

The boy had placed something small among the stones: a dented tin cup filled with water, glistening faintly under the pale sky. It was nothing in the grand scale of the war, just a sip of water. And yet, for those prisoners, it was the difference between life and despair.

The first man to notice the cup hesitated. His hands trembled as he reached down, glancing nervously toward the guards. One wrong move could mean a bullet in the back. Still, thirst overcame fear. He lifted the cup, the metal cold against his cracked lips, and took the smallest sip. The water slid down his throat, cool and clean, reviving a body that had nearly forgotten what it meant to feel alive.

But then something extraordinary happened: he did not drink it all. Instead, he turned and passed it to the man behind him.

One by one, the cup moved down the line. Each prisoner took only a sip, careful not to drain it completely, mindful of the others who still waited. Every swallow was a rebellion against the inhumanity of the march. Every passing of the cup was an act of solidarity stronger than the iron chains of oppression. In a world where survival often meant selfishness, here was selflessness.

The Holocaust stories we inherit often speak of horror, loss, and despair. But woven into them are also these quiet moments of humanity—small acts that shine brighter precisely because of the surrounding darkness. That cup of water was no mere drink; it was a reminder that compassion could survive even in a world designed to extinguish it.

As the cup moved from hand to hand, its physical contents diminished, but its meaning multiplied. The water sustained their bodies, yes, but more than that, it nourished their spirits. It told them they were still human, still capable of kindness and sacrifice. It reminded them that though the Nazis had taken their homes, their families, and their freedom, they had not taken their humanity.

By the time the last sip was gone, the cup had become more than a vessel of water—it was a vessel of memory, carrying within it the strength of unity, the power of compassion, and the stubborn endurance of the human soul.

Remarkably, the guards did not intervene. Perhaps they did not notice, or perhaps they chose to ignore it. Perhaps even they, hardened by years of brutality, felt some flicker of humanity stir inside them as they watched starving men share a cup of water instead of fighting over it. History does not record their thoughts, only their silence. But silence itself, in that moment, allowed kindness to flourish.

When we reflect today on the Dachau death march and countless other atrocities of the Holocaust, it is easy to become overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of suffering. Over six million Jews, along with millions of others, perished in the Nazi genocide. The statistics are staggering, the cruelty beyond comprehension. But numbers, while important, cannot convey the depth of human loss. Stories like the cup of water do.

They remind us that even amid systemic dehumanization, individuals chose compassion. They remind us that survival was not only about enduring hunger and cold, but also about holding onto one’s soul. And they remind us that resistance does not always come through weapons or rebellion; sometimes it comes through something as small and fragile as sharing a sip of water.

The march continued, the cup emptied, but the act of kindness lingered in every heart. Years later, survivors would tell stories of that day, of how one sip of water helped them keep walking, of how passing the cup gave them a reason to hold on one more hour, one more day. That memory rippled outward, carried across generations as part of the collective testimony of the Holocaust.

In classrooms, museums, and memorials, we speak of the brutality of the Nazis, but we must also speak of the courage and compassion of the prisoners. These survival stories are as essential as the record of atrocities, because they teach us not only what humans are capable of in cruelty, but also what they are capable of in love.

In our modern world, where divisions still threaten to pull humanity apart, the story of the cup of water offers a timeless lesson. It teaches us that kindness is not measured by its size but by its impact. A simple gesture, offered in the darkest moment, can light a path for others.

The World War II history that we inherit is not just a chronicle of battles and politics—it is also a moral inheritance. It challenges us to ask: What would we do if we were there? Would we pass the cup?

Every act of compassion we perform today, however small, echoes that same defiance of cruelty. It affirms that humanity endures not in grand speeches or monuments, but in the quiet choice to care for one another.

By the time the sun set on that day in 1945, the prisoners still marched on. Many would not survive the journey; others would collapse along the roadside. Yet each man who touched that cup carried with him more than a sip of water. He carried a memory of shared humanity, a reminder that dignity could survive even in the valley of death.

The cup itself was ordinary, just tin and water. But what it represented was extraordinary. It was proof that in the darkest chapters of Holocaust history, light still flickered. It was proof that in a march designed to break men, compassion kept them walking. And it was proof that even when everything else is taken, the soul of humanity can endure.

And so, the story of the cup of water lives on—not only as part of the record of Dachau, but as part of the record of humanity itself. A reminder, eternal and unbreakable, that kindness, however small, is never wasted.

Note: Some content was generated using AI tools (ChatGPT) and edited by the author for creativity and suitability for historical illustration purposes.